|

Home |

|

|

|

|

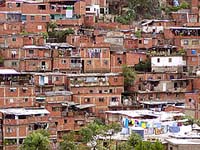

December 12, 2008 Why Chávez Will Ultimately FailIn a world of packaged sound bites and public relations made for television, the image most people have of Hugo Chávez is the one created by his handlers. The real Hugo Chávez is an entirely different person. Not only is the man on the street fooled, members of the US Congress are just as easily fooled. Or maybe not and they are just playing their roles in the scripted drama. After all, most of them too, are made for television personalities. Venezuelan Democracy  Epaulet  Arepa As we went along, people wanted to have more control over their lives. They wanted a decentralized government. They wanted local issues to be settled by the locals, not by the big wheels in Caracas. I call our system a quasi democracy because it was set up in such away that, in fact, we had a two party dictatorship, not a real representative government. We voted but not for the candidates of our choice. We voted for lists made up by the parties. This method guaranteed a certain number of positions to each party depending on the party's voting power. Suppose a certain legislature were composed of 50 elected members. Suppose further that AD was fairly sure of getting 40% of the vote. In practice the top 20 names would be electd and the bottom 30 would not. In such a situation, who do you suck up to, to the voters or to the list makers? Fifty-Fifty  Carlos Andrés Peréz  Arturo Uslar Pietri To make a long story short, by 1992 the popular discontent was strong enough that we had riots and the coup attempt by Hugo Chávez. Democracy was seen as failed and alternatives were proposed. Some, remembering the benign dictatorship of General Marcos Pérez Jiménez, wanted a military government capable of putting the house in order. Others wanted a government of "Notables," the principal proponent being Arturo Uslar Pietri, the man I have called the "Venezuelan Democracy's Undertaker." Through the efforts of Uslar Pietri and Rafael Caldera, a man who hated the sitting president, and with the acquiescence of his own party, Carlos Andrés Pérez was indicted on false charges and deposed. After the interim rule of Ramón José Velásquez, Rafael Caldera bolted his party for refusing to nomiate him for the Nth time and led a coalition of "German cockroaches" to electoral victory. His victory was a clear sign that the people had had enough of the traditional parties that were seen as the source of the country's ills. The Pardon  Caldera during the Chavez swearing in ceremony. To tell the truth, I was surprised. I didn't think Chávez had a chance. Up to then, the radical leftist parties had never been able to garner more than 30% of the vote between them. If memory serves, Chávez won with over 70% of the vote. Now, as I think back on it, I realize that the vote was never ideological but practical: who will give me the most? Of course, the candidtate with the best and most credible promise wins. Splinter parties would never be able to deliver so why vote for them? But when the main parties have proven to be incapable of delivering, you vote for the Messiah! The Chávez Coalition  Luis Miquilena To get elected you need a political machine. AD and COPEY, the two main left of center parties, were not available to Chávez. The available political machinery was the extreme left, those parties that between them had never exceeded 30% of the vote. It was a perfect fit. The left was anxious to feed at the public trough from which they had been excluded and they could use a charismatic leader like Chávez to get there. My upstairs neighbor (who has since moved) is a ranking official in the Chávez regime. He came from one of the socialist parties in the Chávez Coalition. During the height of the 2002 disturbances and discontent I asked him why he supported Chávez. His answer was most revaling. He didn't! "Then what are you doing in the Chávez government?" was my next question. His reply: "I believe in the system." The above pretty much explains what has been happening since 1998. It explains the relation between Chávez and the coalition as well as the relation between Chávez and the military. He does not control either 100%. It is beyond this essay to illustrate the workings of the coalition. Suffice it to say that Chávez has used the carrot and the stick to achieve his aims but when the carrot was insufficient and the stick not threatening enough, a lot of his colatition partners have bolted. The most notorious being his communist mentor, Luis Miquilena. When you study the deeds instead of just listening to the words, it should be loud and clear that Chávez is no ideologue of any stripe. He is ambitious beyond measure and his ambition is to be the President of Venezula for life. Better yet, the second Libertador. Translated into simpler terms, Chávez is a typical Latin American tin-pot dictator. The End of the Road  Student leader Yon Goicoechea  Chávez in Paris  Petare slums Petare is the easternmost part of Caracas. It is a poor sector, at least half being slums. Petare voted against Chávez. If the people felt that Chavez was the champion of the poor, Petare would have been solid Chávez as it has been in earlier elections. The former Mayor of Caracas and ex minister of education, Aristobulo Izturiz, who lost to Antonio Ledezma for the post of Metropolitan Mayor said in a sound bite to the press that Ledezma had not won. Instead, Chávez lost. In this, Izturiz, who is a faithful Chávez ally, can be believed. Denny Schlesinger Uslar Pietri, Venezuelan Democracy's Undertaker |

|

|

|

|

Home |

Top |

|

Copyright © Software Times, 2000, 2001, 2003. All rights reserved |

|